Thomas, Matthew. “Anarcho-Feminism in late Victorian England and Edwardian Britain, 1880-1914.” International Review of Social History 47, no. 1 (April 2002): 1-31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44582675.

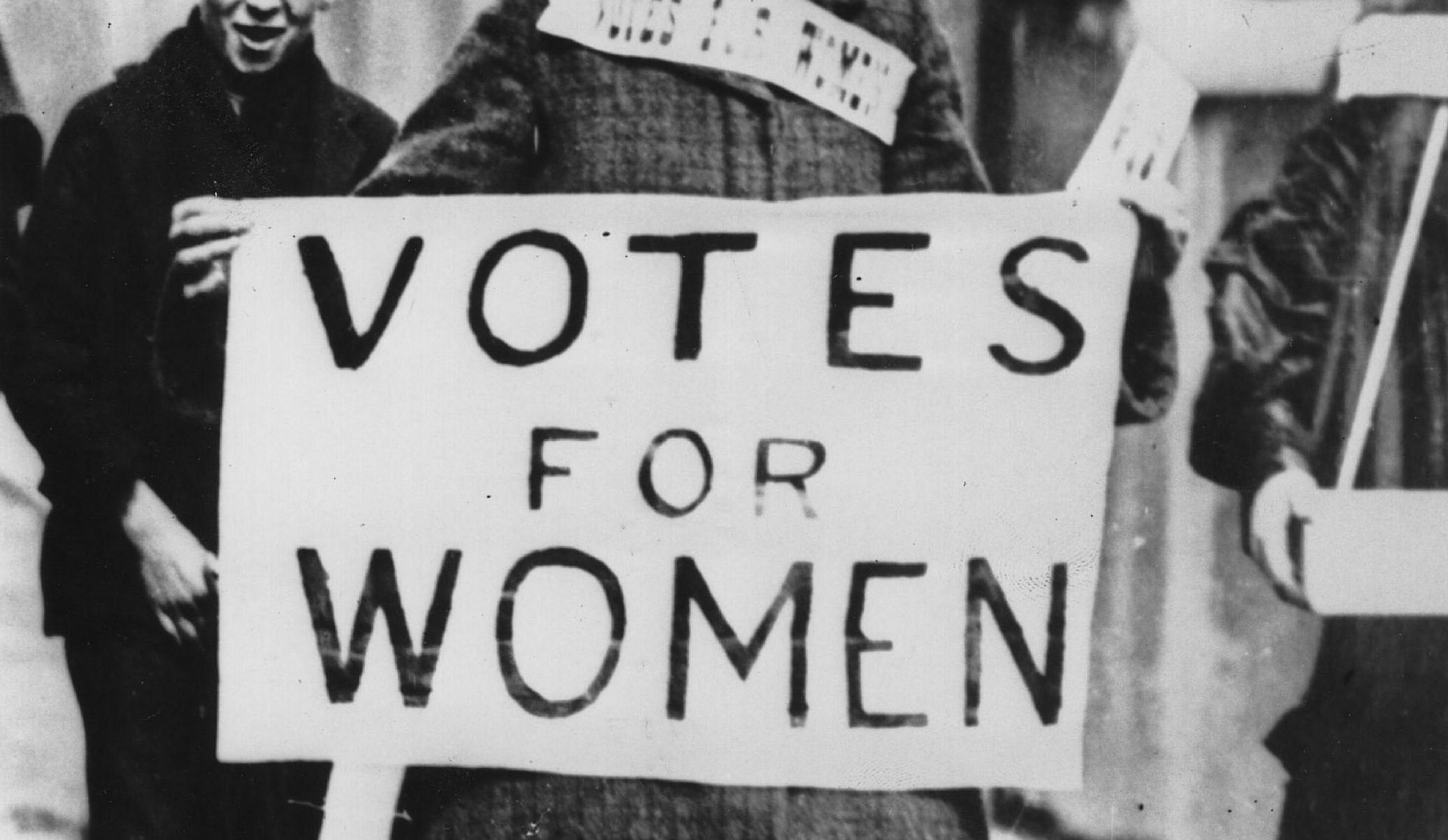

The journal article, “Anarcho-Feminism, in Late Victorian and Edwardian Britain, 1880-1914,” by Matthew Thomas explains the history of the feminist movement in England and how it evolved into the strong miltant movement of the early 20th century. Prior to what we now know as a militant feminist movement, women and women’s rights advocates had been endlessly attempting to obtain rights. For decades, they attempted to infiltrate movements to help push their agendas. But, despite their best efforts, those agendas were pushed aside and/or ridiculed mercilessly. Many different spheres of influence (socialism, communism, liberalism, anarchism), that all could come under the umbrella of feminism were soon united by another influence: anarchism. Anarchism appealed to many women because it promoted the ideas of individual liberty as well as gender equality-among many other things. This anarchism progressed into a militant group of women’s rights activists, who were willing to incite violence to bring attention to their cause. The suffragettes of the time were tired of having to submit to their male counterparts beliefs and orders. They decided to strike out on their own, draw attention to the cause, and finally push forward after far too long of a period of subordinance. This source explains how feminism in the late 19th and early 20th century progressed into a militant movement. The journal article details how the feminist movement during this era originated. Feminists worked tirelessly to just attempt to enter the political sphere, not even originally trying to obtain a vote. They realized their simple request of participation was being ignored, so they decided to fight harder and fight for more. This shows how this fight became the brutal fight that it was.

Rollyson, Carl. “A Conservative Revolutionary: Emmeline Pankhurst (1857-1928). The Virginia Quarterly Review 79, no. 2 (Spring 2003): 325-334. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26440996.

The article “A Conservative Revolutionary…” by Carl Rollyson was written to focus mainly on the life and actions of Emmeline Pankhurst, for she was a central part of the women’s rights movement. Rollyson notes how persistent Pankhurst was in the fight, despite the constant attempt of opponents to stop her. She faced backlash, violence, and imprisonment. But after each of these, she maintained her composure. This article also supports the previous articles argument that the militant feminist movement was born out of empty promises of equal rights. Eventually, the advocates for women’s rights began taking to the streets, caused property damage, made big scenes, and interrupted political events with chants. Pankhurst was at the center of all of this. She believed that women deserved to be not just heard and not only allowed to vote, but to be able to participate in every level of the political process. Yet she herself is a paradox. Rollyson points out that she is extremely radical in some cases, but is exceptionally conservative in others. She was willing to remain unmarried (a scandal at the time), yet disowned her daughter for her communist beliefs. There are some that accused her simply of desiring a fight, any fight. Obviously, it is hard to know her true intentions. But she was a fervent fighter for suffragettes and most definitely progressed the movement rapidly. This source provides a different view of Emmeline Pankhurst, with opinions that are not only praising her. They present her contradictory beliefs, while also highlighting her activism. It paints a more human picture of her, rather than essentially a martyr, full of righteous and correct beliefs, who is willing to die for her cause.

Bearnman, C.J. “An Army Without Discipline? Suffragette Militancy and the Budget Crisis of 1909.” The Historical Journal 50, no. 4 (December 2007): 861-889. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20175131.

In C.J. Bearman’s article, the impending government crisis and political response are detailed as well as how the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union, fronted by Emmeline Pankhurst) intended to respond. During the Budget Crisis of 1909 and subsequent elections and meetings, the WSPU saw this as an opportunity to implant themselves firmly into politics. There were to be plenty of meetings, in which the organization could enter and use as a platform for their agenda. Meetings began to respond to this tactic by enforcing ticket only entry or banning women all together. The suffragettes began to use violence as a means of garnering attention since they were no longer permitted into the audience of meetings. Some original members broke off from the group, since the violence was not controlled by any means. Rather, any level of the organization was allowed to react violently in situations that related to their goals. Although, one historian believes that violence was not encouraged by the head of the WSPU, but if they were to speak out about it, it might undermine their authority if members did not comply. Once the militancy of the group began, it was hard to put a stop to it. This article shows a very different side to the militant suffragette group. Other sources argued that militancy and violence was encouraged because it brought attention to the movement. In this article, it doesn’t say that violence was strictly condoned, but rather it just began occurring and the WSPU decided to adopt that tactic of political movements. Eventually, the violence did become a cornerstone in the movement, for it did gain the WSPU attention from many worldwide. It helped to further their agenda. This argument provides a new view on the movement, while still supporting previous claims.